"We read fantasy to find the colours again, I think. To taste strong spices and hear the songs the sirens sang." -- GRRM

Tuesday 24 July 2012

Eragon

Wednesday 13 June 2012

Solomon Kane

Monday 21 May 2012

Watchmen

Tuesday 10 April 2012

Highlander

In a lot of ways, it's exactly what you'd want from a sword-and-sorcery flick. It has entertaining ideas and a big scope, even if the budget is never quite up to the task. The premise is that there are Immortals among us, who can only die from being beheaded, and they are destined to fight until only one is left, whereupon he will claim the Prize. The hero is Connor MacLeod (Christopher Lambert), a 16th Century highlander, who believes himself to be an ordinary man until he is fatally wounded by the villainous Kurgan (Clancy Brown), but refuses to die. He meets another Immortal called Ramirez (Sean Connery), and is taught the ways of their kind and the rules of their Game. 400 years later, in New York, the few remaining Immortals convene for the Gathering, to fight to the last: there can be only one.

A lot of what makes the premise work is that the film never wastes time explaining it. How do the Immortals know what their task is? Why do the rules of the Game prevent them from fighting on holy ground? How do they know that the last one will claim the Prize? In avoiding explanations, the film never gets bogged down by minutiae, and the mystery over who the Immortals are lends a greater sense of the fantastic and the epic to the film. All the same, it's a very daft film, and probably ought not to work as well as it does. The cinematography is very nice, with the Scottish highlands lending themselves well to the task, but the special effects are a very mixed bag, with wires being clearly visible in many of the fight sequences. This is a particular shame because the fights are actually very impressive, with the duel between the Kurgan and Ramirez featuring possibly the best decapitation ever committed to film. And it would be remiss of me to not mention the thundering soundtrack by Queen, which is just as good as their soundtrack for Flash Gordon and without which the film would not be nearly as enjoyable.

Ropey effects aside, the film's biggest problem is its lead. Christopher Lambert looks the part, but it was on the basis of his looks that he was hired: when he arrived on set, having not met any of the crew before, director Russell Mulcahy discovered that he couldn't speak English, and so he had to learn during filming. This is the source of the bizarre train wreck of what I can only assume is supposed to be a Scottish accent, made even more jarring by having the very Scottish Sean Connery as his mentor. He is also partially blind, which means that his swordfighting is sadly never as good as it could have been. It's a real shame, because Connery and Clancy Brown, despite the latter's voracious devouring of scenery, are very good in their roles, and Lambert seems very subdued and uninteresting compared to them.

All these flaws aside, I do recommend Highlander. It's still one of the better fantasy films that don't star Frodo or Westley, and would probably be remembered as fondly as Conan if the effects had been better and it hadn't been blighted by a string of terrible sequels. Lambert is still a better actor than Arnold, though.

Wednesday 4 April 2012

The Big Lebowski

Sunday 18 March 2012

Speed Racer

Every once in a while, a film comes along that is so terrible that it makes you wonder, if people are able to make something this bad, was anything ever good to begin with? Speed Racer is one such film. An unmitigated catastrophe on pretty much every level, it has the dubious honour of being one of the only films to make me feel physically unwell.

As the above screenshot will hopefully illustrate, the film is a horrible, overdesigned mess whose constant stream of blinding colours will give you a migraine and make you thank whatever God you believe in for the tedious greyish brown of everyday life. There is nothing wrong with bright colours, but when they are in such abundance and the artistic design is so hideous that it genuinely hurts to look at it, there has definitely been a problem. It wouldn't be so bad if the effects weren't awful on a technical level as well, but the omnipresent CGI never fails to unimpress; it is abundantly clear that the set ends about 10 feet behind the actors and everything beyond that point is greenscreen, with potentially impressive cityscapes looking like the flat walls they were projected onto. It's a hideous film. Not in the Gears of War way where everything is drab and boring and indistinguishable from everything else, but in the way that it MAKES YOUR EYES BLEED.

Even if I hadn't been trying to watch the film through a blinding headache, I doubt it would have been any easier to follow. I have no idea what the plot was, since the script is as incoherent and nonsensical as the visuals. I knew I was in trouble when I found out that the main character's name actually was Speed Racer. That aside, there is a monkey (for some reason), who boxes with Speed's younger brother (for some reason). The sequence in question is so bizarre and hallucinatory that I thought I was either asleep, or someone had spiked my drink. I have no idea how it fitted into anything or what its purpose was. Other than that, there is Racer X, who Speed thinks is his brother, but then it's revealed that he isn't, but then it's revealed that he actually is and just had extensive plastic surgery so he is unrecognisable. WHYYYYY?!

There are those who think this film is fun. They are wrong. It's a mess, an impossible to follow catastrophe that makes you want to hit your head against a wall because it would be less painful than trying to watch this drivel. It's one of the worst films I've ever seen. And it's longer than Citizen Kane! It might have been tolerable at 70 minutes, but it instead blunders on for 130.

If you must watch Speed Racer, do so only with friends and a large bottle of industrial strength cider.

Wednesday 15 February 2012

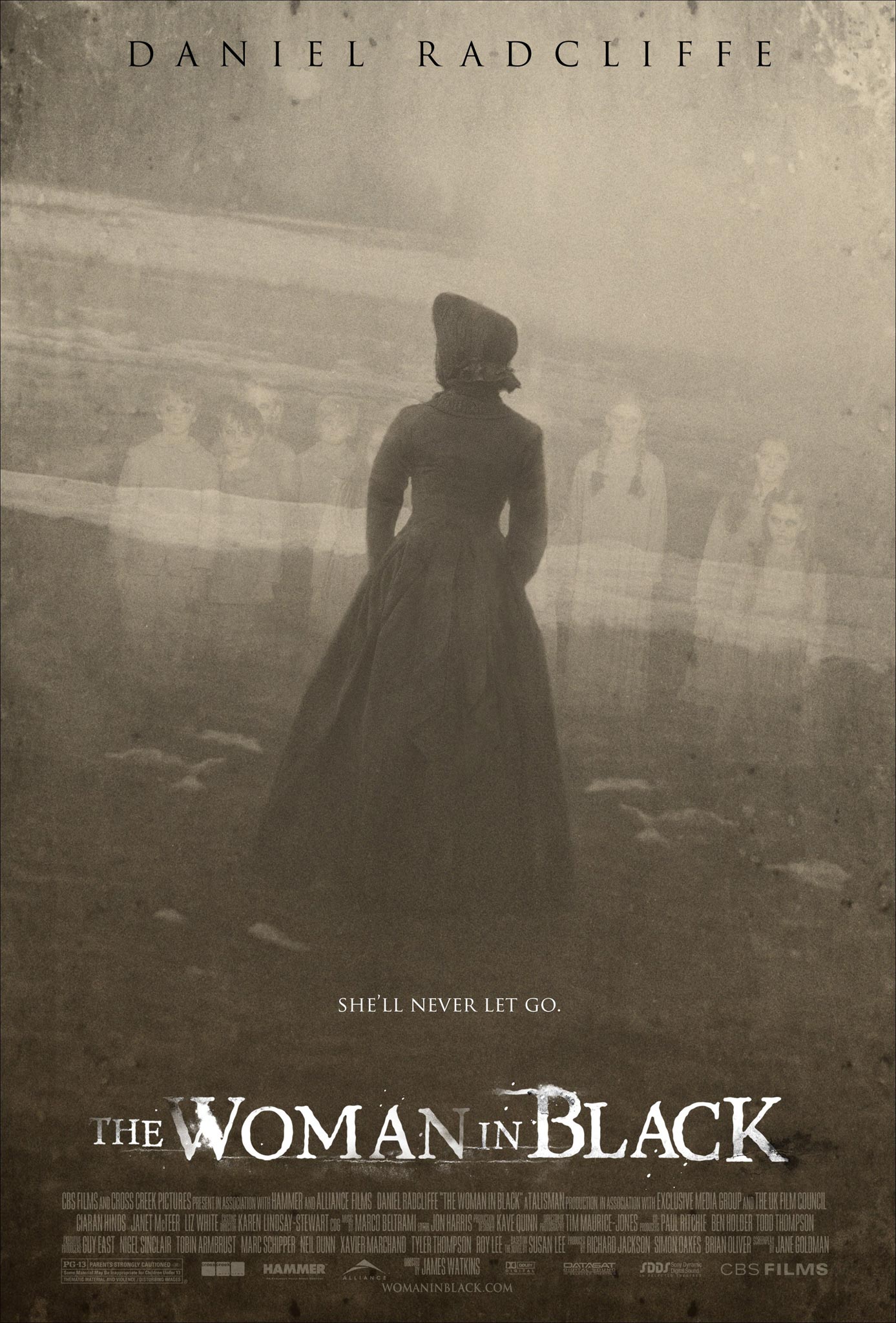

The Woman in Black - What Went Wrong

Let me preface this by saying that The Woman in Black, despite whatever justified reservations you may have about Daniel Radcliffe, is a very good film and you should definitely see it if you get the chance. Special mention has to go out to the set design: Eel Marsh House looks like Satis House after the apocalypse, and the whole film deserves some kind of special award for services to ludicrously creepy children's toys. It makes me happier than I can adequately say to see a horror film which knows that true horror has its roots in tension, suspense and mind games, not blood, gore and titties.

But.

I can't help but think there are, all the same, a lot of areas where it went wrong, and it's been a while since I wrote a negative review, so here goes. I'm going to try and keep spoilers to a minimum, but if it's on your To See list, I'd advise coming back and reading this afterwards.

First and foremost, while you will doubtless be on the edge of, and quite possibly hunched into, your seat for pretty much the entirety of the film, I can't shake the feeling that it just isn't scary enough. Part of this is probably due to knowing more or less what was going to happen, having read the book and seen the play; but that doesn't change the fact that the play is genuinely piss-your-pants terrifying while the film is merely quite scary.

The main part of the problem is a simple one: they show you the titular Woman far too much. She is at her scariest when you only just glimpse her, maybe for only a fraction of a second: the momentary flash of her face seen in a zoetrope, or when she's off to the side of the shot and out of focus. But the filmmakers insist on frequently putting her right in the middle of the frame, often for several seconds at a time, which does nothing but dilute the impact she has. There are a couple of moments towards the end when she runs straight at the camera screaming like a banshee, and yes, it's quite unnerving, but the fright is over as soon as she's off the screen again. In the play, you barely see her, but you feel her presence the whole time and are constantly frightened that she might appear. It's the first rule of horror filmmaking: the less you see of something, the more frightening it is. Our minds will always frighten us more effectively than a film can. This is doubly frustrating because I'm informed that they filmed it in extra-widescreen so they could experiment with putting things right on the edge of your field of view, but they don't take advantage of it nearly enough.

A corollary to this is probably more of a personal problem, I admit, but I wish they hadn't kept showing you the ghosts of the dead children. It's possibly because I love the play's ridiculously minimalist setup (a stage, two men, a box, and the Woman), but I felt like they detracted from the threat of the Woman herself. Every J-horror film made in the last decade has shown us that, yes, dead children are scary, and the trope feels overplayed and unnecessary. Like the Woman, we see far too much of them, and I can't help but feel like it was an just an opportunity to get what are essentially zombies into the film, as if we hadn't already seen enough of them in every book, film, game and comic produced in the last five years. They also cause serious problems with the ending, but I'll get to that in a minute.

*ENDING SPOILERS - DO NOT READ ON IF YOU WANT TO SEE THE FILM*

The ending, it has to be said, is crap. Utter trash. The ending of the play is incredibly depressing and results in you leaving the theatre absolutely terrified, where the ending here is an attempt to give some kind of redemption to Arthur Kipps. Quite apart from the syrupyness of it all, it doesn't make sense in the context of the story. In brief: the Woman makes his son walk in front of a train, Kipps runs to him, they both die. In itself, not bad. Would've been better if Kipps had survived a broken, hollow shell of a man, but still. But then, we see a sequence of Kipps and his son being reunited with his wife in what is presumably Heaven.

It doesn't work. Every indication so far has been that Heaven doesn't exist. The presence of the ghosts of the children killed by the Woman all but outright states that her victims are cursed to be restless for eternity and never find peace. Ciaran Hinds' character tells us the reason he doesn't believe in the Woman is because he wants to believe his son is in Heaven; she does exist, hence her victims cannot go to Heaven. Shortly before Kipps and his son are run over by the train, we hear the woman whisper "never forgive".

Apparently, her final revenge is to grant a tortured soul eternal peace with his beloved wife.

*END OF SPOILERS*

Let me conclude by reiterating my first point: The Woman in Black is a very good film. I'm still not entirely convinced about Daniel Radcliffe, but this was a step in the right direction for him; and Ciaran Hinds is as good in this as he ever is, even if I want to shout "Hail Caesar!" every time he appears on screen. All the same, it could so easily have been so much better. Here's hoping Hammer's next effort doesn't make the mistakes this one made.

Monday 16 January 2012

The Artist